Arthurian Myth continues to be a very popular plot to be explored across TV (Merlin), movies (King Arthur, The Kid Who Would Be King) and comics (Knights of Pendragon, Once and Future), but Liam Sharp’s most recent re-interpretation in Starhenge may well trump the lot of them.

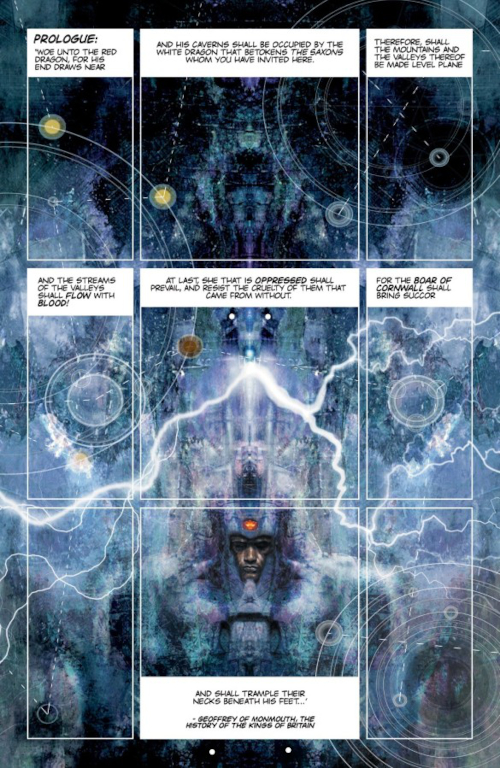

Starhenge seems to be a passion project for Sharp, who has produced the first 6 issue miniseries (collectively titled Book 1: The Dragon And The Boar) entirely by himself; writing, illustrating and lettering (almost) every page. As an artist Sharp has achieved great success over the last couple of decades on best-selling titles such as Green Lantern and Wonder Woman, but this self-owned property is the first time that he has produced anything without the safety net of either a recognised property, a supporting team of creators or a major publisher; and it’s a gamble that he goes all in for. Although the plot is impossible to summarise, Starhenge is a millenia-spanning retelling of the mythical story of Merlin and King Arthur, told across the distant past, present day and far-flung intergalactic future (although not necessarily in that order).

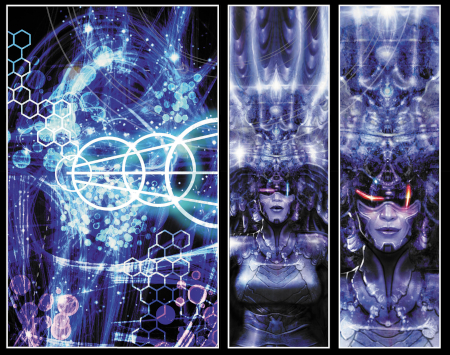

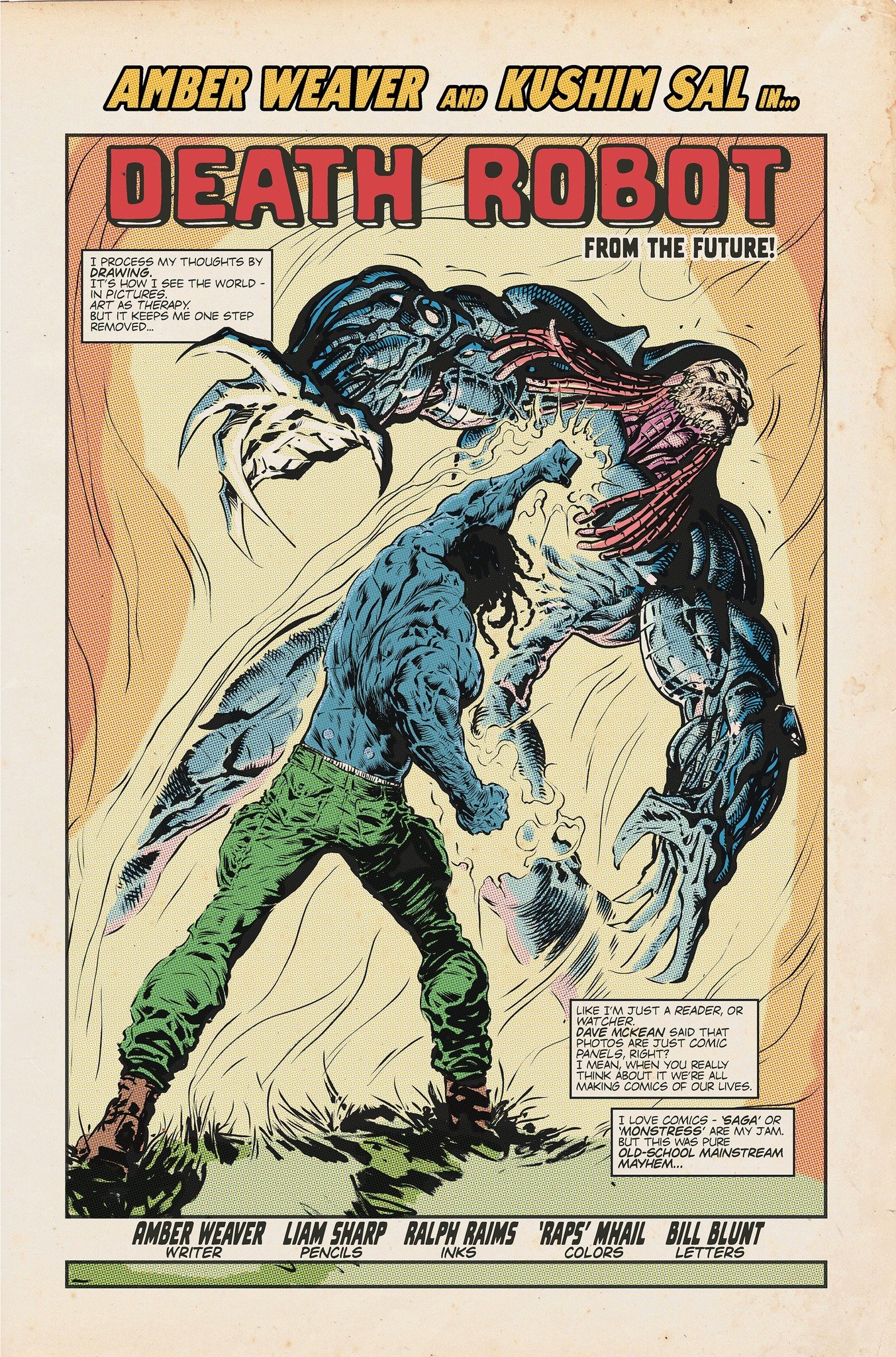

Without a doubt, the main selling point of Starhenge is the visuals; Sharp’s digital painting and ornate page designs are dazzling. Each era in which the action unfolds, whether sci-fi, ancient fantasy or modern contemporary, are portrayed with distinct and masterful textures, ethereal lighting and cinematic scope. He flexes his storytelling further by presenting some of the pages in the style of a pulp fantasy comic, and even recruits his talented daughter Matylda McCormack-Sharp to illustrate a number of cartoon pages and an alternate cover.

Instead of distracting the reader, the different styles are a device to relieve the tension and melodrama of the main plot, and also to provide insight into the backstory of the narrator and main protagonist, twenty-something Brighton-based artist and Wiccan, Amber.

Sharp wrote and lettered the script; and it is admittedly not as polished as his artwork. Narration can be stilted and a bit awkward, the many pop-culture references contrast strangely with the broader mythic themes, and placement of lettering can at times feel alternately cluttered or too spacious.

And yet, these imperfections serve to humanise the narrative; this is a story about storytelling, which is most often done verbally and informally. When Sharp drops in mention of a real-world event from 2022, the reader finds the boundary between reality and fiction blurred, and it’s easy to wonder whether the comics narration is addressing you directly. The result is a reading experience that is more fealt than understood; a story which evolves and unfolds rather than progressing in a linear fashion from start to end.

For more details, see Sharp’s website here.